As the narrative grows that blames foreigners for displacing Costa Ricans through the phenomenon of gentrification, it is worth remembering that it has been precisely foreign hands and minds that co-led the conservation efforts we now proudly showcase to the world.

Marco Villegas. Vice President of the Costa Rican Network of Private Reserves. Executive Director of the Nosara Civic Association

Over the past three years, especially post-pandemic, the word gentrification has become a common way to interpret what is happening in places like Nosara, Monteverde, or Santa Teresa. It is a useful concept to describe the effects of real-estate speculation, but when applied without nuance, it risks erasing an important part of our environmental history: the cooperation between Costa Ricans and foreigners that made the Costa Rican green model possible.

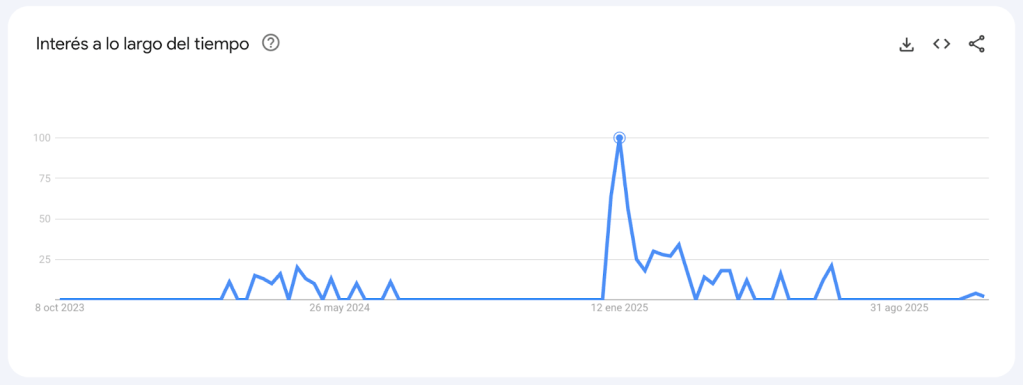

In a quick search using Google Trends, it becomes clear that over the last two years interest in the word gentrification has grown in Costa Rica, with a visible peak in January 2025 which—oh, coincidence!—happens to fall in the same weeks when Bad Bunny released “Lo que le pasó a Hawaii.”

That crossover between pop culture and digital search patterns is no accident: the conversation about gentrification became a trendy topic, a concept many discover through songs or social media rather than through direct experience or study. As it turns out, from January 12 to 18, 2025, searches for the term reached their highest popularity in the past three years, just days after we all started singing “they want to take my river and also the beach.”

Google Trends 2023–2025

If we want to get anywhere, we need to move past trend-driven discussions fueled by the latest viral video on social media.

If we reduce the term to a simplistic slogan, we lose the opportunity to see the full picture: that behind the conflicts over land use there is also a history of cooperation, science, and philanthropy that has sustained conservation for half a century. Instead of fighting over imported labels, we should learn to analyze the phenomenon in its Costa Rican context, where foreigners have not only been buying land for decades but, in many cases, have protected it, reforested it, and placed it at the service of everyone.

Long before wellness retreats or eco-condominiums existed, there were foreigners who came driven by science, spirituality, or the conviction that the forest had to be protected. From the Quakers who founded Monteverde in the 1950s to the families who today maintain reserves in Osa, Nosara, or Sarapiquí, private conservation has been a bridge between worlds.

Of course, not all foreign investment has been virtuous (real-estate speculation is real and it affects us). There are also cases where private interest outweighed the common good, but reducing all foreign presence to that caricature prevents us from seeing the whole

Let’s take a look at it.

The pioneers and institutions that planted the seeds of Costa Rica’s green model

The Costa Rican Network of Private Reserves (RCRN) links more than two hundred private reserves that together protect over 82,000 hectares of forest and natural ecosystems. For decades, private conservation has been a voluntary effort that complements the work of the State, protecting biological corridors, water sources, and critical habitats, while at the same time sustaining rural jobs, supporting ecotourism, and generating environmental education.

One of the organizations that is part of the network—and a foundational pillar of this movement—is the Tropical Science Center (CCT), the first nonprofit organization dedicated to environmental conservation in Costa Rica.

“We are dedicated to the conservation of natural resources through our own system of private reserves and the execution of sustainable development projects focused on the tropical zone. We generate science for conservation, which we apply and disseminate in order to promote a better relationship between humans and nature.” Tropical Science Center.

The CCT provided the scientific and methodological basis for the Costa Rican private conservation model, establishing experimental reserves and laying the groundwork for an applied-science approach to managing tropical ecosystems.

By the late 1990s, the importance of private reserves in Costa Rica had been documented by Patrick Herzog and Christopher Vaughan in the Revista de Biología Tropical (University of Costa Rica, 1998). Their study analyzed 26 private reserves, mostly self-financed and without state support, which together protected more than 10,000 hectares and represented 74% of all the country’s recorded avifauna at the time, including six felid species and most of Costa Rica’s endangered birds. The authors concluded that these private properties—many connected to ecotourism ventures led by foreign and Costa Rican pioneers—complemented state efforts, offering habitat for species not protected in national parks and functioning as buffer zones against the advance of the agricultural frontier.

“The inclusion of private reserves in the national network of protected areas is necessary and urgent… nature tourism can complement government efforts to safeguard biodiversity, but many family-owned reserves will require international technical and financial support to ensure their long-term protection.” Herzog & Vaughan (1998)

That diagnosis, made more than 25 years ago, anticipated the current Costa Rican model: shared conservation between the State, the community, and foreign cooperation.

In Monteverde, that same energy translated into collective action. In 1986, the Monteverde Conservation League (MCL) was born, driven by scientists, educators, and foreign residents together with the local community. Its goal was to protect the cloud forest through direct land purchases and environmental education. From their work emerged the Children’s Eternal Rainforest, an international effort that channeled thousands of donations—especially from foreign schools and families—to secure more than 22,000 hectares of forest. Today, the MCL continues as the custodian of this sanctuary of biodiversity and education and is a member of the prestigious IUCN.

What would Monteverde be without the CCT’s Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve and the Children’s Eternal Rainforest? What would Monteverde be without the determined presence of the pioneering Quaker families who arrived in the 1950s, fleeing what they perceived as a materialistic and militaristic U.S. society?

Let’s move now to Guanacaste and talk about a flagship organization, the Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund (GDFCF), a U.S.-based nonprofit that for over three decades has supported the restoration of tropical dry forest in the northwest of the country. In partnership with the Área de Conservación Guanacaste (ACG), this fund has financed research, restoration, and environmental education in one of the most ambitious conservation projects on the planet. Yes, on the planet!

Its institutional strength is remarkable: according to a 2023 report, the GDFCF managed assets of over 21 million dollars, with revenues exceeding 8 million and an operating surplus of 5 million—figures that reflect its stability and long-term investment capacity. These resources flow directly into scientific programs such as the ACG’s Biodiversity Inventory, which employs local residents as parataxonomists to help identify species, maintains 13 research stations, and develops globally recognized genetic analyses. This level of financial and technical support demonstrates that foreign cooperation has not only protected territories, but has also generated knowledge, local employment, and applied science in service of Costa Rican public conservation.

And of course, we need to talk about my beloved Nosara. The Nosara Civic Association (NCA), founded by foreign families who arrived 50 years ago, today protects 250 hectares of forest currently in the process of becoming a new National Wildlife Refuge, and leads trail projects, land-use planning, and ecological easements. Its transition—from a foreign-led philanthropic organization to a broad and diverse civic body—reflects the maturity of the private conservation movement: integrating conservation into the community fabric.

On the Nicoya Peninsula, the Karen Mogensen Wildlife Refuge also protects more than 960 hectares of tropical dry and humid forest, ensuring water supply for five communities. Its management, driven by international collaboration and local leadership, turns conservation into a tangible common good: clean water, biodiversity, and rural employment.

Further south, Fundación Corcovado developed a model of international philanthropy oriented toward education and environmental restoration; Lapa Ríos, founded by a U.S. couple, demonstrated that tourism can finance conservation without losing authenticity; and Osa Conservation developed a campus of over 3,247 hectares dedicated to applied science, volunteering, and the protection of threatened species.

Completing the loop around Costa Rica, we head to Sarapiquí, specifically La Virgen, to recognize the impact of Tirimbina, a site that combines a reserve, an eco-lodge, and a research center, totaling 350 hectares of forest acquired by Dr. Robert Hunter in the 1960s.

And as if everything I’ve mentioned weren’t enough, we must also recognize the pioneers of the private conservation movement in Costa Rica whose names and projects left a deep mark. Ríos Tropicales, founded by the late Rafael Gallo, former president of the RCRN; Rara Avis, created by Amos Bien, one of the great visionaries of conservation; Curi-Cancha, driven by Hubert and Mildred Mendenhall along with Julia Lowther; and Finca Rosa Blanca, established by Sylvia and Glenn Jampol, are emblematic examples. Added to these are initiatives like Lagarto Eco-Lodge by Vinzenz Schmack, Campanario by Nancy Aitken, Selva Bananito by Jürgen Stein, Reserva Oropopo by Stefano Silvestri, and many other reserves and projects that, from different regions of the country, have woven the network that sustains Costa Rican private conservation today—with a very high component of foreign hands and minds that have loved this land as deeply as anyone.

The Think Tanks

Beyond the reserves, international cooperation planted the institutions that shaped the country’s environmental identity and constitute its brain.

EARTH University, created with the support of foreign foundations, has trained hundreds of leaders in sustainable agriculture since 1990, with a philosophy rooted in entrepreneurship and environmental ethics. The Center for Environmental Law and Natural Resources (CEDARENA) introduced the country to modern environmental law, strengthening legislation and territorial governance. The Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS), founded in 1963 by universities in the United States, Costa Rica, and other countries, consolidated the nation’s role as a living laboratory of the tropics. And CATIE (the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center), with roots dating back to 1940, brought together forestry, agricultural, and climate research under a single purpose: sustainable development.

Millions of dollars for conservation

The impact of foreign communities on conservation can be measured in multiple dimensions—through their cultural influence, the hectares of land they protect, or the thousands of jobs they generate—but without a doubt, direct investment is visible every day through the multimillion-dollar donations injected into the country year after year.

According to data from the organization Amigos of Costa Rica, which channels donations from more than 60 countries to a large number of nonprofit organizations in the country, in 2024 the donations sent to Costa Rica totaled around $11.6 million, of which 25% went directly to organizations in the conservation category. Overall, after the pandemic, the funds this organization channels into Costa Rica have nearly tripled.

The guardians of wildlife and the sea

In recent decades, international support has also manifested in wildlife rescue and applied environmental education. Organizations such as International Animal Rescue (IAR) and Sibu Wildlife Sanctuary—both with strong volunteer participation and foreign backing—work on the care, rehabilitation, and release of animals injured by road collisions, electrocution, or illegal trafficking. Their work, in coordination with SINAC and local communities, has made it possible to return hundreds of monkeys, sloths, toucans, and other animals affected by human expansion back to the wild.

On the Caribbean coast and the Nicoya Peninsula, centers like the Jaguar Rescue Center and Marine Restoration embody the same spirit of cooperation, but oriented toward environmental education. The Jaguar Rescue Center has transformed empathy for wildlife into a comprehensive volunteer and education program for thousands of visitors, while Marine Restoration promotes coral nurseries, coastal monitoring, and awareness about the state of the oceans.

These initiatives—with undeniable contributions and momentum from foreigners, whether through their founding, project support, or donations that fund their operations—are contemporary examples of civic conservation: efforts that combine technical knowledge, community commitment, and a vision of shared well-being between humans and nature.

The new challenge: to integrate, not deny

El desafío actual no es negar el aporte extranjero, sino lograr que los nuevos residentes- particularmente quienes llegan con alto poder adquisitivo- se integren al tejido social y natural que ya existe. Ese tejido fue construido por generaciones de costarricenses y por pioneros que, viniendo de otros países, apostaron por hacer de Costa Rica un lugar mejor.

La reciente nota de la BBC sobre el arribo de millonarios digitales y expatriados de alto perfil refleja este nuevo escenario: Costa Rica se ha convertido en destino global para inversionistas que buscan naturaleza, estabilidad y prestigio verde. Pero esa atracción trae una responsabilidad.

A estos nuevos actores, la conservación costarricense les lanza un llamado claro: no basta con comprar tierra o construir bajo estándares sostenibles; es necesario pertenecer. Participar en las comunidades, apoyar redes locales de conservación, fortalecer fondos colectivos y aportar a la gobernanza ambiental.

Si las primeras generaciónes de extranjeros vinieron a proteger, esta nueva debe venir a multiplicar ese impacto. No como observadores externos, sino como parte de una comunidad ecológica y humana que lleva más de medio siglo demostrando que la diversidad puede ser una forma de desarrollo.

Costa Rica no se conservó a pesar de los extranjeros, sino con ellos. Ese “con” sigue sThe current challenge is not to deny the foreign contribution, but to ensure that new residents—particularly those arriving with high purchasing power—integrate into the social and natural fabric that already exists. That fabric was built by generations of Costa Ricans and by pioneers who, coming from other countries, chose to make Costa Rica a better place.

The recent BBC piece about the arrival of digital millionaires and high-profile expatriates reflects this new scenario: Costa Rica has become a global destination for investors seeking nature, stability, and green prestige. But that attraction comes with a responsibility.

To these new actors, Costa Rican conservation issues a clear call: it is not enough to buy land or build under sustainable standards; it is necessary to belong. To participate in communities, support local conservation networks, strengthen collective funds, and contribute to environmental governance.

If the first generations of foreigners came to protect, this new one must come to multiply that impact. Not as outside observers, but as part of an ecological and human community that has spent more than half a century proving that diversity can itself be a form of development.

Costa Rica was not conserved in spite of foreigners, but with them. That “with” remains the verb that defines our future. And today’s call is not one of exclusion, but of shared responsibility: that those who arrive with resources also arrive with purpose, and understand that true luxury does not lie in owning nature, but in protecting it together with others.iendo el verbo que define nuestro futuro. Y el llamado hoy no es de exclusión, sino de responsabilidad compartida: que quienes llegan con recursos también lleguen con propósito, y que comprendan que el verdadero lujo no está en poseer la naturaleza, sino en protegerla junto a los demás.

Leave a comment