by Marco Villegas.

I first came to Nosara on a family trip back in 1992, at a time when getting here felt like a journey to the end of the world, and the hours spent in a Land Rover Santana were the most anticipated adventure of the year. After crossing half a dozen rivers, we would camp out and then head back to San José. Over the years, I kept coming back, and that coming and going unexpectedly led me to become a resident and an active member of the community.

I’m talking about Nosara, Costa Rica — a trendy tourist destination that has the luxury of ignoring the usual formula of District + Canton + Province + Country. Just saying “Nosara” is enough.

And as a resident of this popular destination, it was inevitable for me to try to understand the dynamics I witnessed every day. This article is the result of some personal reflections, readings, testimonies, and data I’ve gathered or accessed over my time in Nosara. It basically tries to answer a few simple questions: What is happening in Nosara? Have these same dynamics played out elsewhere in the world? What lessons can we learn from other places? And are we still on time to care for this magical place?

Richard Butler’s Theory of the Tourism Area Life Cycle (1989) says that every tourist destination goes through six stages: exploration, involvement, development, consolidation, stagnation, and rejuvenation (or decline). It’s an easy way to understand how tourist spots evolve: first a few people arrive, interest grows, investment kicks in, it becomes popular, saturation hits, and then comes the uncomfortable question: Do we save it or let it fall apart? It seems Nosara is well along this path and is now entering the hardest part of the movie — where every step and every decision become crucial for its survival.

Let’s start with a quick recap.

There was a Nosara before the American Project.

Some historians say that “Chorotega” means “the people who escape.” It’s a fitting name for this context. We know that Nosara was once a quiet valley, inhabited between 500 BC and 300 AD by people who migrated from Mexico and buried their dead with musical instruments high up on the hills — between 50 and 150 meters above sea level (Las Huacas area, for example) — always overlooking the ocean. At the Río Rempujo site, archaeologists have found flutes and pottery shaped like armadillos, crocodiles, monkeys, birds, turtles, and big cats. Music as a bridge between the earth and the afterlife.

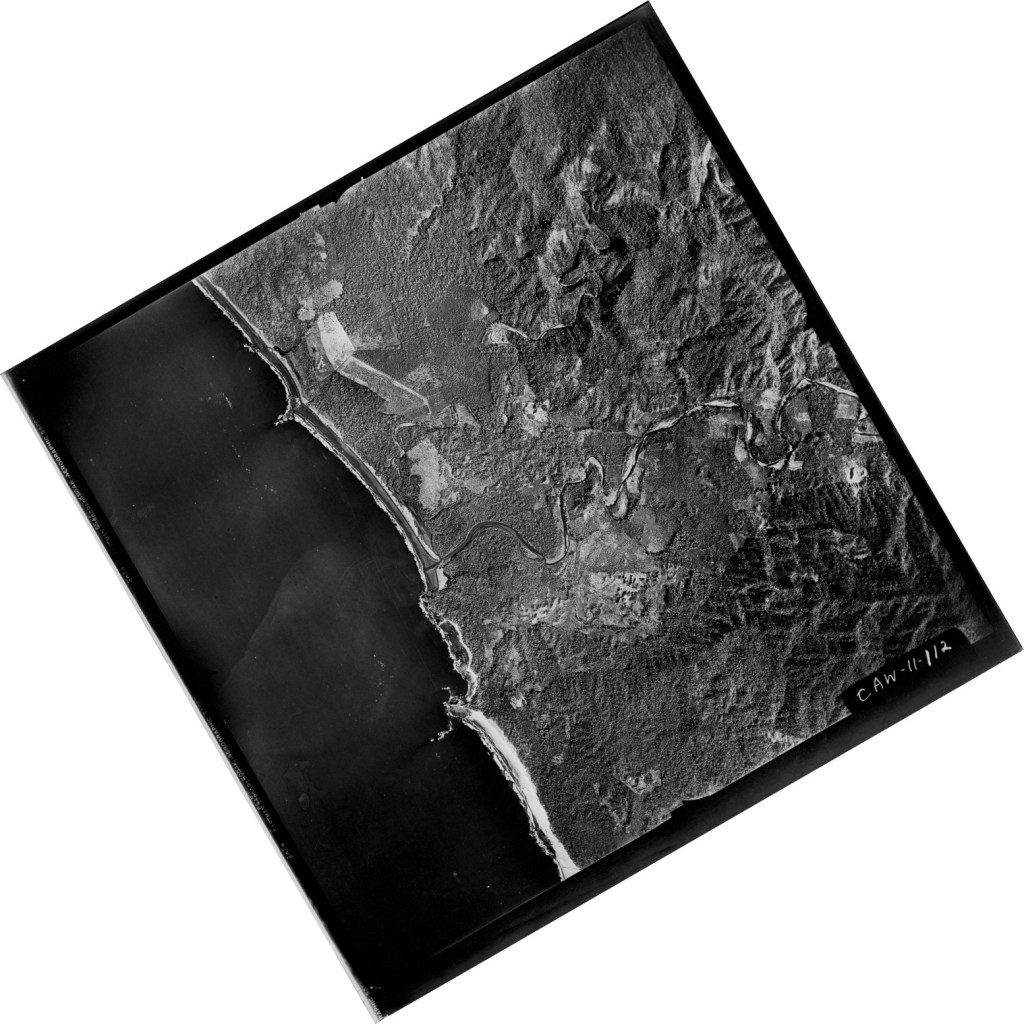

And although Nosara has a long and beautiful coastline, it didn’t have major coastal indigenous settlements like other parts of Costa Rica, such as Papagayo. Why? “The lack of bays prevented a similar development to other settlements” wrote archaeologist Frederick Lange from the University of Colorado after his excavations in the 1970s. Lange was the first to confirm this with evidence: Nosara didn’t populate the same way because the sea here offers no shelter — only power. That same force would later attract thousands of tourists to ride the waves of Guiones.

The first people to see this land from the sea were conquistadors, pirates, and marine cartographers. Probably the first “nao” to sail past Nosara was commanded by Andrés Niño, a Spanish conquistador who sailed from the Gulf of Nicoya northward toward Nicaragua in 1522. Later, in 1685, the English pirate Bartholomew Sharp wrote about sailing from the Gulf of Nicoya to Cabo Velas, guided by a map stolen from the galleon Nuestra Señora del Rosario, which already marked the “Cape Guyones.”

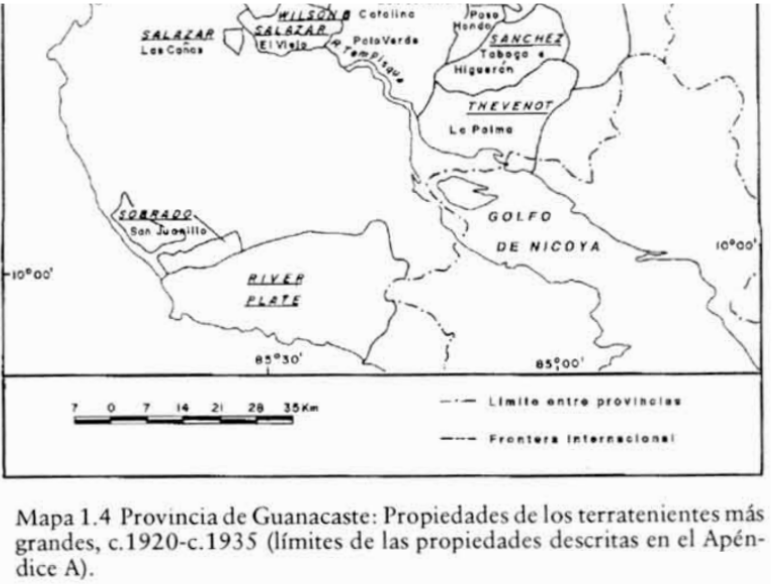

As part of Costa Rica’s negotiations with investor Minor Keith and the United Fruit Company (a pioneer in creating the so-called Banana Republics), the entire territory of Nosara was titled in 1894 as the “Nicoya Lot” by the River Plate Trust Co., a British company with a timber exploitation contract negotiated with Keith. 55,600 hectares were titled. In other words, the first time Nosara’s lands were titled, it was to give them to a foreign company.

Then came the pioneers. Families from different parts of Nicoya arrived in search of land, in an era when fencing off a piece of land was enough to be considered its owner. That’s how the Arrieta, López, Montiel, Avilés, Juárez, and Noguera families arrived. These are some of the main families still considered “true Nosareños” today, because like in any community with a degree of isolation, the last to arrive are always “the outsiders” — and there’s always someone who’s “not from here.”

Among them was Filemón Baltodano, a rancher from Corralillo de Nicoya, owner of vast land holdings and a powerful figure in the area. Baltodano had his own airstrip, built under somewhat dubious conditions. He would fly in on his small plane, order crops to be planted, and fly the harvests out. Some locals used to say he “had a pact with the devil.” In 1928, Law No. 135, promoted by a relative of his in Congress, created the “Nosara Road,” opening up the first trail between Sámara and Nosara.

Baltodano Ranch became the main hub of Nosara’s cattle industry (located near today’s gas station). Some elderly women in Nosara today recall working as cooks at the ranch, and that sometimes, workers were paid only with food.

It was a different Nosara. By 1930, there were an estimated 130 people. People lived off cattle, the river, and their machetes. By the 1940s, it was a land of “small ranches.” There were already at least 12 farms, each ranging from 35 to 48 hectares, owned by families like the Matarrita, Ugarte, Rosales, Obando, Ruiz, Gómez, Silva, among others.

Before the first foreigners arrived, the “Chepeños” had already come. These were visitors from San José who had their beach houses — doctors, lawyers, and middle-upper-class families. Among them was Dr. Longino Soto Pacheco, a famous Costa Rican cardiologist who landed his small plane on Playa Guiones and, according to locals, helped the community free of charge. A 1956 photo shows the Soto Pacheco brothers heading to the beach.

The women who once cooked at the Baltodano Ranch gradually set up their own small eateries (sodas) to serve visitors. Gasoline was available in only one place, brought in metal barrels. Everything was basic, homemade, and direct. But in that precariousness, there was community. There was connection. One of the key features of this stage, according to Butler’s model, is that local communities start offering basic services to visitors: sodas, improvised lodging, informal guides. A rudimentary infrastructure emerges, making it easier for the first travelers to stay — creating intense interactions between locals and visitors.

Besides Guiones Beach, there’s of course the beautiful Pelada Beach. Before the “gringos” arrived, there was an era when it was famous for women who swam nude there, or at least topless. Some elderly locals say that’s why its original nickname was “Las Peladas.” (Naked Beach)

Isolation was the norm. To leave, people used a pier in Garza, from which boats departed for Puntarenas on trips that could last up to 12 hours.

Exploration Phase: This is the stage characterized by minimal infrastructure, preserved natural surroundings, and only a few adventurous tourists seeking authentic experiences. There’s no real tourism infrastructure yet, and the local community strongly maintains its traditions.

That’s how Nosara began in the 1960s and 70s.

“Fortunately, the owner of the Nosara Ranch was willing to sell it at an attractive price. I was also lucky enough to buy several smaller lots that added up to an extra mile of beautiful beach.” — Alan Hutchinson

Hutchinson, founder of the so-called Playas de Nosara Project of 1,110 hectares, envisioned an ecologically balanced development. The original designs included a large amount of green areas to be left as nature reserves. Apart from Baltodano’s lands, he bought plots from over 60 owners, many of whom abandoned the area after the cattle ranches closed down. Although an 18-hole golf course and over 700 lots were planned, the project faced serious financial problems. Legend has it that Hutchinson went bankrupt, left Costa Rica in 1975, and never returned — sparking conflict over land use and compensation for people who had bought plots.

Also in 1975, those first foreigners who had bought lots from Hutchinson founded the Nosara Civic Association (NCA) to organize and provide basic water, electricity, road maintenance, security, and conservation services that had been promised to them. It wasn’t until 1982 that one of the first class-action lawsuits over disputed lands was resolved.

Little by little, the beach became a more prized asset, and over time some people tried to restrict access. One elderly woman recalls that a group of foreigners tried to close off part of the beach, and they had to ask the Bishop for help to prevent it. What used to be just cattle fields by the sea became increasingly valuable with the arrival of the American Project.

These stories reflect an initial stage where the destination was just starting to be discovered, and where tourism had not yet completely transformed local life.

Involvement Phase. Locals begin to offer basic services (lodging, food). A budding form of tourism organization starts to appear.

One key aspect of this stage, according to Butler’s model, is that local involvement and control over development start to decline rapidly. In this phase, new residents begin to take the lead in planning and decision-making, and local communities shift from being active hosts to spectators of growth. In Nosara, this change is reflected in the creation of two key organizations: the Asociación de Desarrollo Integral de Nosara (ADIN), driven by local actors, and the Nosara Civic Association (NCA), initially founded and led by foreigners who started to play a direct role in managing basic service provision for the town.

This is how what is now the current NCA office used to host essential community services: from an electric plant, to the first high school in Nosara, and even the Nosara Fire Department headquarters (the only independent firefighters in Costa Rica, Bomberos de Nosara).

The 1980s were decisive for Nosara, mainly because of two major milestones: the expansion of the Ostional Wildlife Refuge to include the Guiones and Pelada sectors, giving the beaches permanent protection in 1985; and the creation of the Nosara District in 1988, officially recognizing the community as a distinct entity within the Nicoya canton. It was also in the 80s that the Nosara airport, a post office, a police station, and the ICE office officially opened, with help from the NCA.

Phases 3 and 4. Development–Consolidation. New foreign investors arrive in Nosara. The destination starts becoming popular. Hotels are built, roads are developed, and the local dynamic changes.

At this stage, the number of tourists and foreign residents begins to rival that of local residents. Tourism is no longer a novelty; it’s an industry. And with that, pressure on resources, local culture, and the natural environment intensifies. Tourism clearly becomes the main economic driver. The oldest hotels are sold and remodeled by their new owners. The idea of “how great the community used to be before” is heard more and more often.

Those hotels originally founded by the first foreigners are sold and remodeled (Gilded Iguana, Harmony, Giardino, among others).

And so, little by little, the pressure keeps increasing. The number of foreigners grows but the community’s capacity to handle these needs does not necessarily grow with it. Infrastructure falls far behind, including roads, electricity service, or even the capacity of local organizations to stay active and relevant to address this new community reality.

More recently, from 2020 to 2022, the built area in Nosara increased by 209%. In that same period, more square meters of swimming pools (13,418 m²) were built than social housing (1,769 m²). There are almost 1,000 properties on Airbnb and the public school operates at 180% of its capacity (State of Nosara Report 2024). The local water boards (ASADAS) are at their limit. Guiones and Pelada use 619,000 m³ of water per year. Every day, Nosara lives its two sides: a luxury zone and a town with basic needs.

At this stage, according to Butler’s model, tourist arrivals reach their peak and environmental, social, and economic problems become more evident. Infrastructure starts showing signs of saturation, and conflicts between visitors, residents, and ecosystems become more acute.

The State of Nosara Report (2024) says it clearly: unprecedented growth and economic opportunities, but also structural inequality, loss of natural habitats, overcrowding, and displacement.

So, what can we expect for the future? The experience of dozens of tourist destinations like Nosara shows us two stages that are coming — or may have already begun: a stagnation and subsequent decline in which problems worsen and the destination goes out of fashion; or a rejuvenation of the community, based on strengthening its social fabric.

Tulum: The Mirror We Don’t Want to See Ourselves In. Tulum was once a bohemian paradise now turned chaotic tourist hub, where unchecked luxury swallowed the town. Nosara still has a chance not to repeat it, but some reflections are eerily similar.

Tulum was once the epitome of alternative tourism: ecological, laid-back, spiritual. Today, it’s a distorted postcard of itself. Between LED lights, sky-high prices, drug money laundering, and community displacement, it became a perfect example of how lack of control, unplanned growth, and romanticizing the “natural” can distort a place until it becomes unrecognizable.

Between 2000 and 2020, Tulum’s population grew from 6,733 to over 33,000 people, fueled by internal migration attracted by the tourism boom and real estate speculation. That unplanned, overflowing growth left marks: displacement, service collapse, environmental destruction. The paradise was sold so well, it was lost.

And so, inevitably, decline sets in.

Despite the similarities — a small coastal town, barely explored at first, that suddenly becomes fashionable and starts growing exponentially beyond its capacity — Nosara is still on time to avoid following Tulum’s example.

In the end, the answer lies in our own capacity for cooperation. If we achieve community collaboration that overcomes the division between Nosareños, Chepeños, and foreigners, and if we build a shared agenda that combines public and private efforts to solve our challenges, Nosara can still look forward to a promising future.

If we manage our resources wisely, plan with vision, and organize responsibly, Nosara will not only remain a refuge for those escaping the world’s chaos but also an example of a living community, aware and proud to care for itself. May our story not be just about those who escape, but about those who stay to protect what we have in common.

Nosara, June 15th, 2025.

Dedicated to my father, a true history enthusiast and the one who brought me to Nosara for the very first time

Fuentes:

Asociación de Adulto Mayor de Nosara. (2023). Entrevista a adultos mayores. Entrevista no publicada.

Asociación Cívica de Nosara. Informe Estado de Nosara (2024)

Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica. (s.f.). Decreto N.º 33: Contrato con la compañía River Plate Trust. Recuperado de

http://www.asamblea.go.cr/sd/SiteAssets/Lists/Consultas%20Biblioteca/EditForm/DecretoNo.%20%2033%201097.pdf

Bellin, J.-N. (1754). Carte de l’Amérique Méridionale. París: Dépôt des Cartes et Plans de la Marine.

Gutiérrez, A. (s.f.). Relatos orales sobre la Hacienda Baltodano y la figura de Filemón Baltodano. [Testimonio oral].

Lange, F. (1971). Estudios arqueológicos en el valle de Nosara. Universidad de Colorado.

Obtur Caribe – Universidad de Costa Rica. (s.f.). La colonización agrícola de la región atlántica caribe costarricense (1870–1930). Recuperado de

https://obturcaribe.ucr.ac.cr/documentos-publicaciones/articulos-cientificos/sociedad/299-la-colonizacion-agricola-de-la-region-atlantica-caribe-costarricense-1870-1930/file

Servicio Hidrográfico de los Estados Unidos. (1890). Aviso de Navegantes: Observaciones del USS Thetis en la costa del Pacífico costarricense. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Hydrographic Office.

Soto Pacheco, M. (1956). Archivo fotográfico personal. [Fotografía de los Hermanos Soto Pacheco en Playa Guiones].

Universidad de Costa Rica, Escuela de Antropología. (s.f.). Prácticas de enterramiento en el sitio arqueológico Rempujo (G752 Rj) durante el período Tempisque (500 a.C.—300 d.C.).

Leave a reply to Charles Herwig Cancel reply